Of the many things we at Geneva Global find interesting about the news: it all happened without a staff of program officers to identify and vet the grantees. Scott’s news followed in the footsteps of Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey similarly deploying hundreds of millions in philanthropic capital in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, using a publicly accessible Google Docs spreadsheet to make the disbursements transparent. Like Scott, Dorsey has no formal philanthropic infrastructure behind his giving.

So, are “traditional” foundations with professional staff and program officers passé? Does Scott’s and Dorsey’s recent giving suggest that all donors should prioritize speed and responsiveness, forgoing the costs of sustaining a professionalized grant making machine in order to enact change more quickly and support organizations who may otherwise have been overlooked? Count us as a cautious “maybe.”

Grantmaking nuances

The argument in favor of professional staff and grant makers is fairly straightforward: by hiring the right domain experts, you (as the donor) hope to ensure your dollars will go to the most impactful organization and programs. In the absence of those professional gatekeepers, donors run an increased risk of funding good pitches rather than good projects or organizations, being unaware of trends in the field that should inform their grant making, and potentially chasing flashy fads rather than more structural reform efforts. Program officers serve as a form of philanthropic hedging; by investing in staff, donors reduce the risk that things go sideways within a grant portfolio and also, hopefully, achieve some degree of synergy where the whole of the portfolio is greater than the sum of its (individual grant) parts.

Kelsey Piper’s piece in Vox does a nice job of pushing back on that conventional wisdom:

“But there’s a good argument that at least some funders should be happy to make lots of grants, many of which may disappoint them anyway. Vetting often adds lots of overhead, delays, and communication problems for charities; a faster process that gets money where it’s needed sooner can make a big difference. In some specific fields (say, scientific research), studies have shown that all the effort-intensive work to find the “best” grants is fairly arbitrary; researchers don’t agree with each other’s rankings at all. In a case like that, you might as well just get money out the door, with minimal vetting — as Scott has done.

And in some areas, like coronavirus relief, getting money to people quickly is really important. If it takes months to make a grant and more months for the money to arrive, it may be too late to help. Scott donated to GiveDirectly, a nonprofit that gives people cash, no strings attached, and which has dramatically expanded its operations this year in order to help people around the world deal with the coronavirus crisis.”

But there are some nuances missing in this narrative. First, while it’s true that both Scott and Dorsey have given away impressive and important sums in a short amount of time, neither has done so in a vacuum of advice and referrals, despite the lack of professionalized staff behind the scenes. Dorsey, for example, has seemed to lean heavily on advice from Rihanna’s Clara Lionel Foundation for co-funding opportunities (see Column G of his famous spreadsheet) while Scott may have benefited from the Giving Pledge’s network of peer donors and support staff at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which helps staff the Pledge (disclosure: Geneva Global supports teams at the Foundation).

A risk with these referral-based approaches to rapid giving (“I’m giving to XYZ and you should too!”) is that they have the potential to reinforce many of the existing biases in philanthropy. Most of the grantees selected by Scott and Dorsey are skilled at strategic communications and networking, and have physical and professional presence in the Global North (where most philanthropic capital is concentrated). They are skilled fundraisers as well as skilled change agents; while the two are not necessarily in conflict, they help explain in part why philanthropic donors—especially large institutional foundations and ultra-high net worth individuals—tend to circle around the same cluster of grantees and partners. We sometimes fail to appreciate the positive contribution of the professional program officer who can help push back on these implicit (and sometimes explicit) biases by advocating for broadening the grantee base rather than doubling down on “tried and true” programs and organizations.

Goal-Informed Decision-making

We’re privileged to work with both some of the world’s largest institutional philanthropies (which often boast dozens or even hundreds of professional program officers) as well as smaller and medium-size private and family foundations with no staff, or where the principal donors themselves serve as de facto staff. In that cumulative experience, we’ve found there’s unsurprisingly no “right” answer to whether a donor should or shouldn’t invest in a professional staff to guide their grantmaking. As Stanford professor Rob Reich correctly points out in the Vox piece, the recent Scott and Dorsey news “weakens the case that giving away $1.7 billion is difficult…[but] there remains a question about whether it’s difficult to do well.”

How would we guide donors asking that question of themselves? Again, there’s no formulaic approach to arriving at the right answer, but we’d start with:

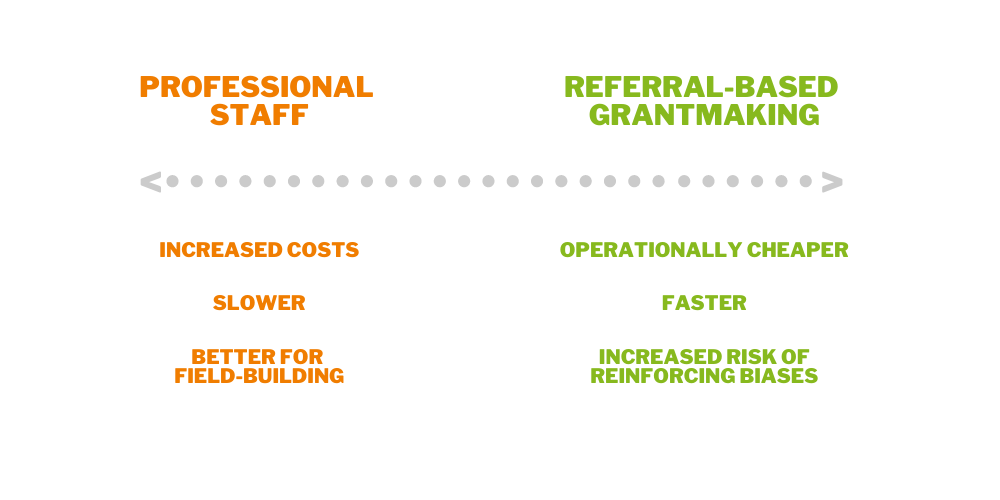

- Is your giving primarily for humanitarian relief or emergency response? If so, you might want to think about using trusted referrals more than a permanent professional staff, given the importance of speed and agility in your grantmaking.

- Are you interested instead in field-building efforts and/or intentionally prioritizing granting to organizations that are new, not well known, or off the beaten path? A professional staff might indeed be the way to go, at least in part.

These are less zero-sum binary questions and more of a spectrum of consideration for donors to wrestle with:

Effective giving is as much art as it is science, with timing and luck playing no small role in whether a given grant helps stimulate positive social change. Time will tell if program officers and a professional staff remain important parts of that story.